Food deserts and transit

Imagine your car breaks down and repairing it is not an immediate option. How close is the nearest grocery store to you? Could you walk there? Would you need to take the bus? How long would it take you to get there by bus? How will you feed your family? Is the nearby food from the gas station or convenience store really nutritious enough to keep your kids healthy?

This is a reality that many Charlotteans face. Recently, there has been a lot of focus within the Charlotte community upon food deserts and areas of inequality within our city. A food desert is defined by the USDA as a Census tract that is both:

- Low income: a poverty rate of 20 percent or greater, or a median family income at or below 80 percent of the statewide or metropolitan area median family income

- Low access: at least 500 persons and/or at least 33 percent of the population lives more than 1 mile from a supermarket or large grocery store (10 miles, in the case of rural census tracts).

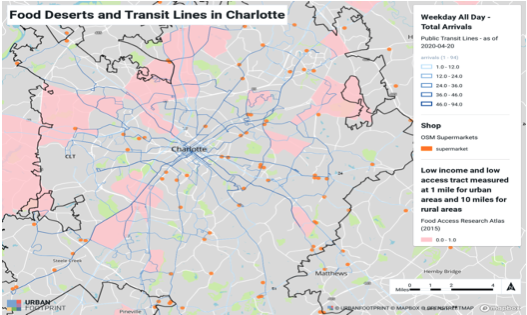

Almost 15% of Mecklenburg’s population lives in food deserts. This is a greater percentage than both the national average (11%) and NC average (13%). As an organization invested in supporting sustainable economic and environmental systems, Sustain Charlotte frequently partners with neighborhoods to advocate for more efficient public transportation and policies that reduce problematic urban sprawl. Using a software called UrbanFootprint, we identified the areas of Charlotte that are both food deserts and have little access to public transportation.

UrbanFootprint analyzes cities in terms of land and water use, zoning, transit lines/stops, and even environmental characteristics such as invasive plant growth. It is a powerful tool that Sustain Charlotte has recently gained access to through a Mobility Data for Safer Streets (MDSS) grant from Spin. We are currently exploring how to best use this tool to advocate for smarter growth and environmental as well as economic sustainability.

Without a reliable source of nutritious food near their neighborhoods or a way to get to a grocery store without a car, many Charlotteans are forced to buy less healthy (and often more expensive) food from nearby gas stations and convenience stores. This promotes obesity rates and other chronic diseases as well as costs more in the long run, further limiting economic mobility. Widespread obesity also negatively affects the economy, costing the US healthcare system $147 billion a year.

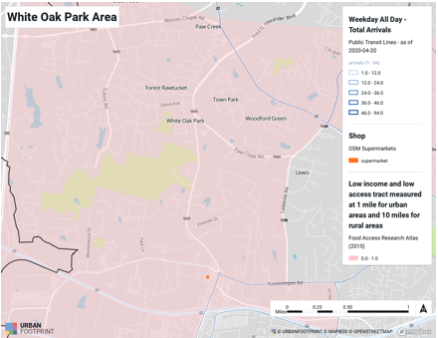

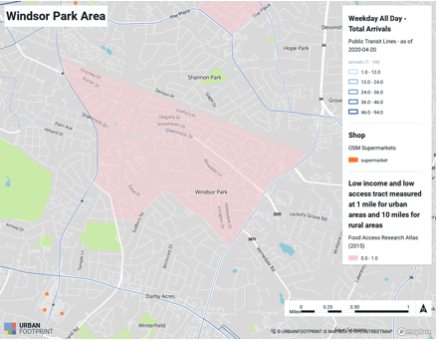

As shown here, the White Oak Park neighborhood in northwest Charlotte and Windsor Park neighborhood in east Charlotte are some of the most affected by a lack of transit and supermarkets. The closest supermarket is miles away from most people living in these neighborhoods. This distance incentivizes a car-centric lifestyle. People in these areas must either walk miles to get to a grocery store or nearest CATS bus stop, find a ride with someone, or take on the expense of buying and maintaining a vehicle. According to AAA, just owning a car costs $8,500 on average annually.

In food deserts, which are often low-income areas, many people can’t afford to buy or own a car. When forced to do so, they become financially burdened by it, further decreasing their economic mobility. That extra $8,500 could go towards education, home ownership, retirement savings, or any other financial decision that improves quality of life.

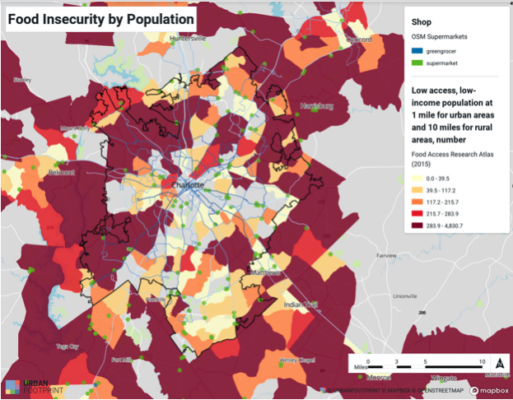

When examining food insecurity by population instead of census tract, it becomes even clearer that Charlotte is facing a hunger crisis. Much of the dark burgundy on the map above has few transit lines running through it, and grocery stores are few and far between. The sprawl underlying this pattern has contributed to deforestation, increased carbon emissions, and the undermining of the “ten-minute neighborhood” concept, especially in the northern and southwestern neighborhoods. Without addressing these food deserts and the inequality that comes with them, Charlotte will continue to be a city divided by poverty and a lack of economic mobility.

We also talked with residents in the Lakeview neighborhood in west Charlotte, who confirmed that many of their neighbors struggle with access to grocery stores. Fortunately, there is a CATS bus line that runs along Rozzelles Ferry Rd, but it still makes for a long roundtrip just to buy food and necessities.

Some of the burgundy areas are underdeveloped and don’t have grocery stores or public transit. Detractors of extending bus lines to underserved areas say that this extension would be inefficient and a waste of resources, as the areas that are least served often have less economic activity happening. However, if there is no transit in an area then economic development often won’t happen at all and a grocery store will never be built. Transit lines are key motivators of development and allow people to break the cycle of povertythrough increased opportunity and cheaper transportation expenses. Ideally, transit would be available to every neighborhood in Charlotte, but until we have the resources to achieve this ideal, it should be strategically placed to serve those who need it most.

This article was researched and written by Xavier Gomez, a UNCC Charlotte student interning at Sustain Charlotte in summer 2020. Xavier’s internship was sponsored by the Levine Scholars Program.

Sources

https://ui.uncc.edu/story/charlotte-mecklenburg-urban-food-desert

Thanks for reading!

As a nonprofit, community support is essential for us to keep doing what we do — including providing free articles like this. If you found this article helpful, please consider supporting Sustain Charlotte.

Want to stay in the loop? Subscribe to our weekly newsletter and follow us on Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter.